Categories: Customer Service

By Mark Tomalonis

Principal, WarehouseTWO, LLC

Which of these statements best describes your company’s approach when quoting to your customer a “promise date” for an item currently not in stock?

Which of these statements best describes your company’s approach when quoting to your customer a “promise date” for an item currently not in stock?

"If we don't quote the promise date that our customer wants, we will lose the order."

"If we keep over-promising and under-delivering, we will lose the customer."

Which approach is better?

The two approaches are that of a “promise date optimist” and a “promise date realist”, respectively. I side with the realist. Sometimes, when you are a realist, you may have to be a “padder”. That is, you may have to “pad” (i.e., add significant additional time to) a supplier’s quoted lead time, to determine a more realistic “promise date” to your customer. And sometimes, you may lose an order, in the interest of maintaining your customer’s trust.

A supplier’s quoted lead time is the time period from order entry date to ship date from the supplier. That value alone does not determine a “promise date” to your customer.

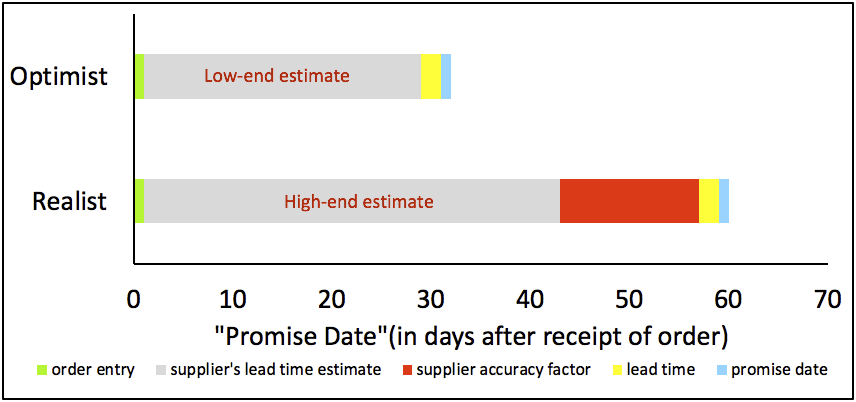

When a supplier quotes to you that the lead time for a backordered item is, say, “4-to-6 weeks”, what “promise date” to you commit to your customer? Consider the two scenarios illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Supplier’s Lead Time Estimate of "4-to-6 Weeks" Versus Your “Promise Date”

Below are details on how each “promise date” in Figure 1 above was calculated.

In its most optimistic view, “promise date” is the order date plus these additional time components:

order entry date

+ supplier’s quoted lead time (days; the minimum of the quoted range)

+ inbound transit time (days)

+ outbound transit time (days)

= promise date

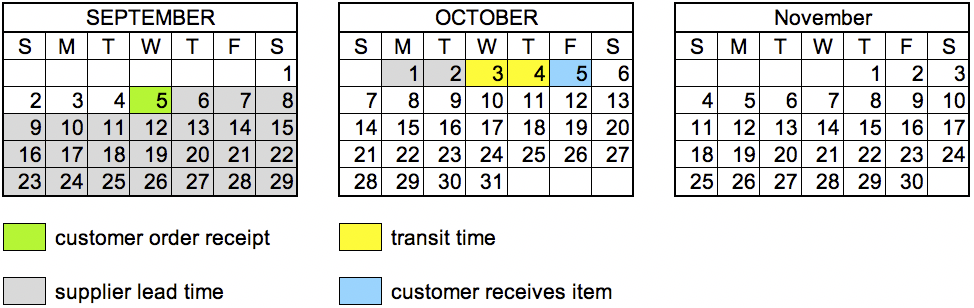

Example: You get the customer’s order on September 5th. Your supplier has quoted a lead time of “4-6 weeks”. Because you are an optimist, you believe “4 weeks”. You add two transit days, one for overnight inbound shipment and one for overnight outbound shipment. (Big spender, you.) Your calculated “promise date” is October 5th. This is illustrated in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Example Optimist’s “Promise Date”

Calculate “promise date” using the above method, and you will be a hero to your customer. But only on the day that you take the order will you be a hero.

I recommend that you be a realist when quoting to your customer a “promise date”, by including a “supplier accuracy factor”:

order entry date

+ supplier’s quoted lead time (days; the maximum of the quoted range)

+ inbound transit time (days)

+ outbound transit time (days)

+ “supplier accuracy factor” (“padding”; days)

= promise date

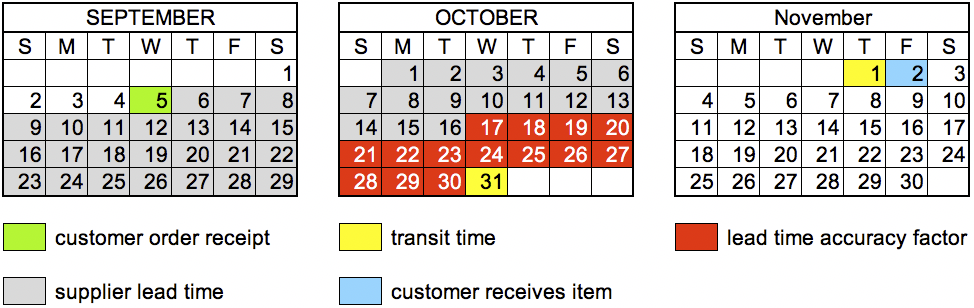

Example: You get the customer’s order on September 5th. Your supplier has quoted a lead time of “4-6 weeks”. Because you are a realist, you believe “6 weeks”. You add two transit days, one for overnight inbound shipment and one for overnight outbound shipment. (Again, big spender, you.) Then you add a “supplier accuracy factor” (“padding”), based on your supplier’s historical performance versus quoted lead times. Your calculated “promise date” is November 2nd. This is illustrated in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3. Example Realist’s “Promise Date”

Calculate “promise date” per the above, and you might disappoint the customer. But if you meet or exceed this commitment, your reputation will remain intact in the eyes of that customer. Think, “under promise, over deliver”.

A “Supplier Accuracy Factor” is your “padding” to adjust what your supplier tells you, into what you can say to your customer in confidence.

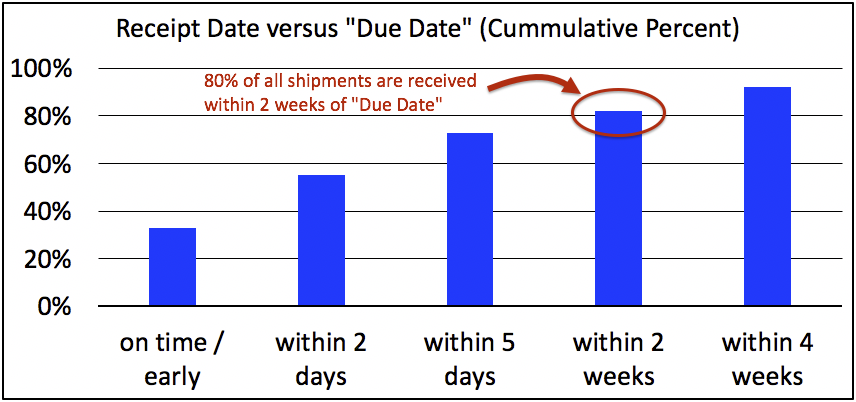

How accurate are your suppliers’ quoted lead-times? And is your answer to this question merely qualitative (“really bad!”), or is your answer quantitative based on actual results measured over time (“during the last six months, 73% of this supplier’s shipments arrived within five days of promise date”)?

If you are not already doing so, you ought to be measuring your suppliers’ delivery performance against initial lead time quotes or promise ship dates. This is the classic “supplier on-time-delivery” metric. While there are several ways to measure your suppliers’ on-time-delivery performance, I recommend this method:

Step 1: Capture “Original Promise Ship Date”. This is the ship date based on the original lead time quoted by the supplier at the time of purchase order placement. If given a lead time range (e.g., “4-to-6 weeks”), choose the longer lead time. Updated or revised “promise dates” from suppliers should never be used to measure accuracy of the original “promise date”. Moving the target may help you predict when you are going to receive the item, but it does nothing to improve the accuracy of measuring a supplier’s performance.

Step #2: Calculate “Due Date”. This is equal to the supplier’s promise ship date plus transit time, which is based on whatever freight method you choose.

Step #3: Select several time-spans of “lateness”. As a start, consider the ones shown below. (Of course, choose time-spans appropriate for your business.)

on-time / early

within 2 days of promise date

within 5 days of promise date

within 2 weeks of promise date

within 4 weeks of promise date

Step #4: Determine the "Supplier Accuracy Factor", in days, based on an acceptable “Confidence Factor”. A confidence factor is the percentage of all line items shipped from the supplier that arrive within a tolerable time-span of the lateness relative to the originally calculated “Due Date”.

Figure 4 below shows a sample supplier on-time-delivery metric and a proposed "confidence factor" of 80%. In this example, the resulting “Supplier Accuracy Factor” is two weeks, or fourteen (14) days.

Figure 4. “Supplier Accuracy Factor” Calculation.

No one wants to wait (double-digit?) weeks for anything. If your company participates in "inventory-sharing" with peer wholesaler-distributors, and another distributor has in stock what your customer needs, you can ignore all of the complicated lead-time calculations above. Instead, if the item is in stock somewhere in your peer distributor network, then it is “in stock” for your customer. Thus, your "Promise Date" calculation is:

promise date = TOMORROW

Not yet participating in “inventory-sharing” with peer distributors? I can help get you started. Contact me at mark@warehousetwo.com.

About the Author After a successful career in sales and operations management in the wholesale-distribution industry, Mark Tomalonis is now principal of WarehouseTWO, LLC. He amuses himself by writing articles such as this one, to help wholesaler-distributors execute their operations better. Mark’s articles and tips are published in WarehouseTWO’s monthly e-newsletters. Click here to subscribe.

After a successful career in sales and operations management in the wholesale-distribution industry, Mark Tomalonis is now principal of WarehouseTWO, LLC. He amuses himself by writing articles such as this one, to help wholesaler-distributors execute their operations better. Mark’s articles and tips are published in WarehouseTWO’s monthly e-newsletters. Click here to subscribe.

About WarehouseTWO

WarehouseTWO, LLC is an independent “inventory-sharing” software tool created exclusively for durable goods manufacturers and their authorized distributors, and for any group of durable goods “peer” wholesaler-distributors, such as members of a buying/marketing group or cooperative. To learn how inventory-sharing with WarehouseTWO can help your business, visit the WarehouseTWO website, or email info@warehousetwo.com.